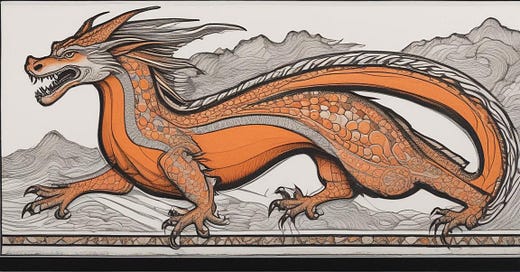

There was a dragon in the lake, for that is where they dwell. Once, it had protected the waters for the people who lived nearby. Now, corrupt and greedy, it poisoned them.

Its demands at first were fair: a sheep each month to abate its hunger would suffice to keep the air and waters clean and keep the serpent at bay. But dragons fed get fatter, and the fatter they get, the hungrier. The demand for one sheep soon became two. Not long, and the dragon tired of mutton, and started to crave finer meats. Children were its favoured fare. The townsfolk first resisted, but what were they to do, when they could not drink the water or breathe the air? To keep things fair, they chose by lot, and offered up their choicest tots. Until, that is, the lot fell to the fairest of them all: the princess of the realm.

By this time, the people’s fear had turned to worship. The King was no exception. Much as he loved his daughter, he revered the beast more, and as long as he kept feeding it, the people stayed alive to pay their taxes. And though it was sad that she would be the bride of no mortal man, what greater honour could he give her than to wed her to his god? Her consumption would be the consummation of the pact between his earthly kingdom and the dragon’s spirit realm. The dragon would surely protect the nation ever more for such a noble boon.

The victim was dressed in nuptial white and processed along the virgin road with fanfare to the altar of the dragon’s lair. A kiss of farewell from her father and the ceremonies complete, the party left her veiled to meet her groom alone. The wedding night drew near.

The groom emerged, cold, fat body sliding from its hole, hot breath smoking from its vast, fanged maw. The princess, trembling, steeled herself to yield. But it was not her doom that day to enter the dragon’s maw. For a saint of God had pitied her, and rode swiftly to her aid. The serpent saw the soldier take his sword and make the dread sign, the sign Moses made to defeat its kin, the half-demon sons of Amalek; the sign by which the Victim tricked the prince of snakes, leapt into his throat and cut his belly open from within, freeing swallowed souls; the sign of Jonah; the Sign of the Cross. Too late did it recoil, as the holy man spurred forth and dug deep into its side with his spear.

Wounded, chained, tamed, the dragon meekly followed the princess and the saint back to the town. The people saw their idol for the beast it was. In return for its slaughter, they turned to the saint’s God, whose holy sign had saved them from slavery and death. For where the dragon died, a spring of pure water suddenly began to flow, and in it were they baptised and purged of their murderous blasphemies. The King who had been content to sacrifice his daughter built a shrine church to the Holy Mother around the well as penance. It is said the waters flow there still for healing.

But what of the saint? His greatest work was yet to be done. For though he had killed one dragon and saved one city, the worshippers of the dragons were yet legion, and among them the Emperors of Rome. Fearing him, they killed him, among many other thousands. But his death was not in vain. St George and the many martyrs fanned the flames of faith which spread throughout the lands. Within decades, the reign of the demons was overthrown, as a new Emperor crossed the Milvian bridge under the same life-giving sign, written for him in the clouds.

This, at any rate, is my somewhat embellished version of the tale. It was not new even when it was first told. It shares key elements with many ancient pagan dragon-slaying stories. For this reason, moderns have tended to pooh-pooh it. It has been told so many times, in so many cultures, is so universal in its motifs, that it simply must be false, they reasoned. Their reasoning seems naive. Surely its ubiquity is all the more evidence for the truths it holds? And lest this appeal to tradition set Protestant hackles on edge, the same can be said for its biblical precedents. The serpent in Eden, the taming of Leviathan, the cosmic battle with the dragon in Revelation: all these share commonalities with pagan myths, and Leviathan is drawn directly from them. This makes the story no less true.

But how can it be true, you say, when we know that there are no such things as dragons? Show me one, and I will believe it is there. But don’t ask me to believe in invisible things, in scaly spirits of chaos and corruption. Because nowadays, of course, no kings or presidents send their children or ours out as sacrifices to dragons to preserve their status and power. No parents feed their children to chaotic spirits beyond their control because, well, everyone else is doing it. Or are we so sure? Are there things we cannot see, intellects and agencies uncontrolled by human agency in any straightforward way, the implacable forces of escalating war, the invisible hand behind the markets, the algorithms of social media, the voracious data devourers of AI? Are we sure that we are not feeding dragons? And feeding them, most of all, our young?

St George’s Day every year fuels predictable column inches of affected outrage: because someone somewhere is celebrating something else instead, or because the flag-waving is jingoistic and outmoded, or because St George is too English, or not English enough. Politicians “reclaim” the red and white flag from the hooligans who seem only to exist in the televised fantasies of Guardianistas [edit: and by politicised police forces looking to paint patriots as fascists]. We are reminded that to be truly English is to be flagless, above that sort of thing, really not a nation at all, just an empty vessel variously filled over our long and nefarious history by the latest band of marauders. But both sides miss the point. The point is to slay dragons.

Patron saint of England and of many nations, St George is not to be remembered only for his foreignness, as some token of multiculturalism, as some preachers will no doubt today expound. Nor yet is he the exclusive preserve of my or any worldly nation. A soldier of Christendom and subject of the Kingdom of Heaven, he serves something greater. And that is what we English at our best could be. Through our nation, through our flag, not in spite of either, we can be citizens of a nation wider than the world, one that exceeds all space and time.

Let us wave the flag, but only if we really believe in the sign it bears. Let us pledge our lives to that sign. For England will find greatness only in service of the greater Kingdom, as a nation which stands against the dragons which corrupt and pollute this world. At the very least, let us stop feeding the dragons that are consuming our society and protecting the corrupt. Let us worship the One who can slay in us the dragons of disorder, ambition, and desire, who can free us from the serpents to whose poison we are addicted. For that, we need the prayers of Our Lady and St George. We need to venerate our patron saint and call on him for aid in spiritual battle. But above all, we need the sign of the Cross, by which Our Lord tricked the Devil of his due, and which strikes fear into the heart of all the serpents’ slaves.

Great! Beautifully said! The best sermon I ever read about Saint George!

Fr. Franco Sottocornola, Shinmeizan