This is the third post in a series of commentaries on the Mystical Theology of Dionysius the Areopagite: click for parts 1 and 2.

Thus, then, the divine Bartholomew says that Theology is much and least, and the Gospel broad and great, and on the other hand concise. He seems to me to have comprehended this supernaturally, that the good Cause of all is both of much utterance, and at the same time of briefest utterance and without utterance; as having neither utterance nor conception, because It is superessentially exalted above all, and manifested without veil and in truth, to those alone who pass through both all things consecrated and pure, and ascend above every ascent of all holy summits, and leave behind all divine lights and sounds, and heavenly words, and enter into the gloom, where really is, as the Oracles say, He Who is beyond all. For even the divine Moses is himself strictly bidden to be first purified, and then to be separated from those who are not so, and after entire cleansing hears the many-voiced trumpets, and sees many lights, shedding pure and streaming rays; then he is separated from the multitude, and with the chosen priests goes first to the summit of the divine ascents, although even then he does not meet with Almighty God Himself, but views not Him (for He is viewless) but the place where He is. Now this I think signifies that the most Divine and Highest of the things seen and contemplated are a sort of suggestive expression, of the things subject to Him Who is above all, through which His wholly inconceivable Presence is shown, reaching to the highest spiritual summits of His most holy places; and then he (Moses) is freed from them who are both seen and seeing, and enters into the gloom of the Agnosia; a gloom veritably mystic, within which he closes all perceptions of knowledge and enters into the altogether impalpable and unseen, being wholly of Him Who is beyond all, and of none, neither himself nor other; and by inactivity of all knowledge, united in his better part to the altogether Unknown, and by knowing nothing, knowing above mind (nous).

Theology is much and the least: Dionysius attributes this expression to the Bartholomew, though it appears in no extant texts associated with the name of that Apostle. There was once, apparently, an apocryphal Gospel of Bartholomew, which St Jerome cautioned against treating as genuine; fragments of a probably late 5th-century text called the Questions of Bartholomew exist, suggesting a now lost Bartholomeian tradition to which Dionysius may have been alluding. This, I think, is more satisfactory than the common suggestion that he is deploying Bartholomew’s name as a ruse to preserve the illusion of his own sub-apostolic pseudonym. We should note that while the word “theology” can mean simply “Scripture” in the CD, it is also a compound of theos and logos, the Divine Word. Parker’s decision to leave the word untranslated preserves that ambiguity. Taking “theology” in the latter sense, one can find a somewhat speculative connection to the Questions of Bartholomew, at the point when Bartholomew asks the Blessed Virgin Mary how it was possible for her to conceive the Divine Word in her womn, which is to say, to contain the uncontainable vastness of God in the minutest, literally embryonic form:

“Thou that art highly favoured, the tabernacle of the Most High, unblemished we, even all the apostles, ask thee … to tell us how thou didst conceive the incomprehensible, or how thou didst bear him that cannot be.” (Questions of Bartholomew II.4)

The Divine Word is indeed much and least, when incarnate in the Virgin’s Womb. Yet Our Lady refuses to answer:

“Ask me not concerning this mystery. If I should begin to tell you, fire will issue forth out of my mouth and consume all the world” (Ibid., 2.5)

– which, indeed, starts to happen, until Jesus appears and puts His hand on his mother’s mouth! Inexplicable, it seems, this mystery must be received in silence, or as Dionysius puts it, without utterance. I do not suggest that this tenuous link suffices to claim that Dionysius directly had this passage of the Questions in mind. However, given that Bartholomew has traditionally been associated with Nathaniel, to whom the Lord promised visions of “heaven opened, and angels ascending and descending on the Son of Man” (Jn 1:51), it is not too outrageous to suggest that the name of Bartholomew was associated with such mystical experience as Dionysius attributes to him here, and fits Dionysius’ overall authorial practice rather better than the theory of mere pseudonymous name-dropping.

So, in what does Bartholomew’s “supernatural” intuition consist? Once again, on the necessary balance between kataphasis and apophasis, the simultaneous eloquence and silence of the Good Cause of all, who is both poly-logos and a-logos, “many-worded” and “no-worded,” multiform and formless, abundant in rationality and yet beyond reason.

Thus, to approach the Cause, one must pass through (dia-bainein) consecrated and pure things, and pass beyond (hyper-bainein) all Ascents (anabaseis), including the divine lights and heavenly words (logoi), to enter into the gloom/cloud (gnophos). Here we see the typical Christian Platonic paradigm of purification, illumination and perfection, commonly referring respectively to the Sacraments of Baptism, Chrismation/Confirmation and Holy Communion. In Baptism, one is cleansed of sin; in Chrismation, illumined by the light of the Spirit; and in Communion, brought into oneness with God.

Dionysius follows the great Cappadocian father Gregory of Nyssa’s pattern in making Moses the “type” or model of this three-stage ascent. Hence Moses is first purified, separated as the baptised are from the catechumens; then he is illumined by pure and streaming rays of God’s light; and finally reaches the summit. This is not, however, just a recipe for individual spiritual exercises. Moses’ role is elucidated in Dionysius’ Ecclesiastical Hierarchy, where the imagery here deployed in the description of his ascent is applied word-for-word to the liturgical role of the Hierarch or Bishop. This means that for Dionysius, ascent to God is never a merely individual spiritual quest, but can be arrived at only through the collective body of the Church. The Bishop, as representative of Christ’s Headship, lifts up and leads the rest of the Body into God’s presence.

The summit of divine ascent is portrayed in terms of sight and contemplation (theōria). However, even at the summit, Dionysius cautions that Moses does not see God Himself, “for he is unseeable” (atheatos gar). Rather, Moses sees only God’s place (topos). This is arguably an extension of Gregory of Nyssa’s teaching of epektasis, “straining towards” (q.v. Phil 3:13). For Gregory, since God is love and God is infinite, to be one with God’s love is to part of an inexhaustible and insatiable movement of desire, eros. It is the desiring itself, constantly leading us towards God, that is the reward: there is no static satiation, no “boredom” in heaven, but rather an unending and entirely fulfilling love with which we can never be overfilled. Hence Moses only ever sees God’s “backside,” because one can only ever follow after God, never stand in front of Him: the Beatific Vision is the vision of where God has gone before or, in Dionysian language, His “place.”

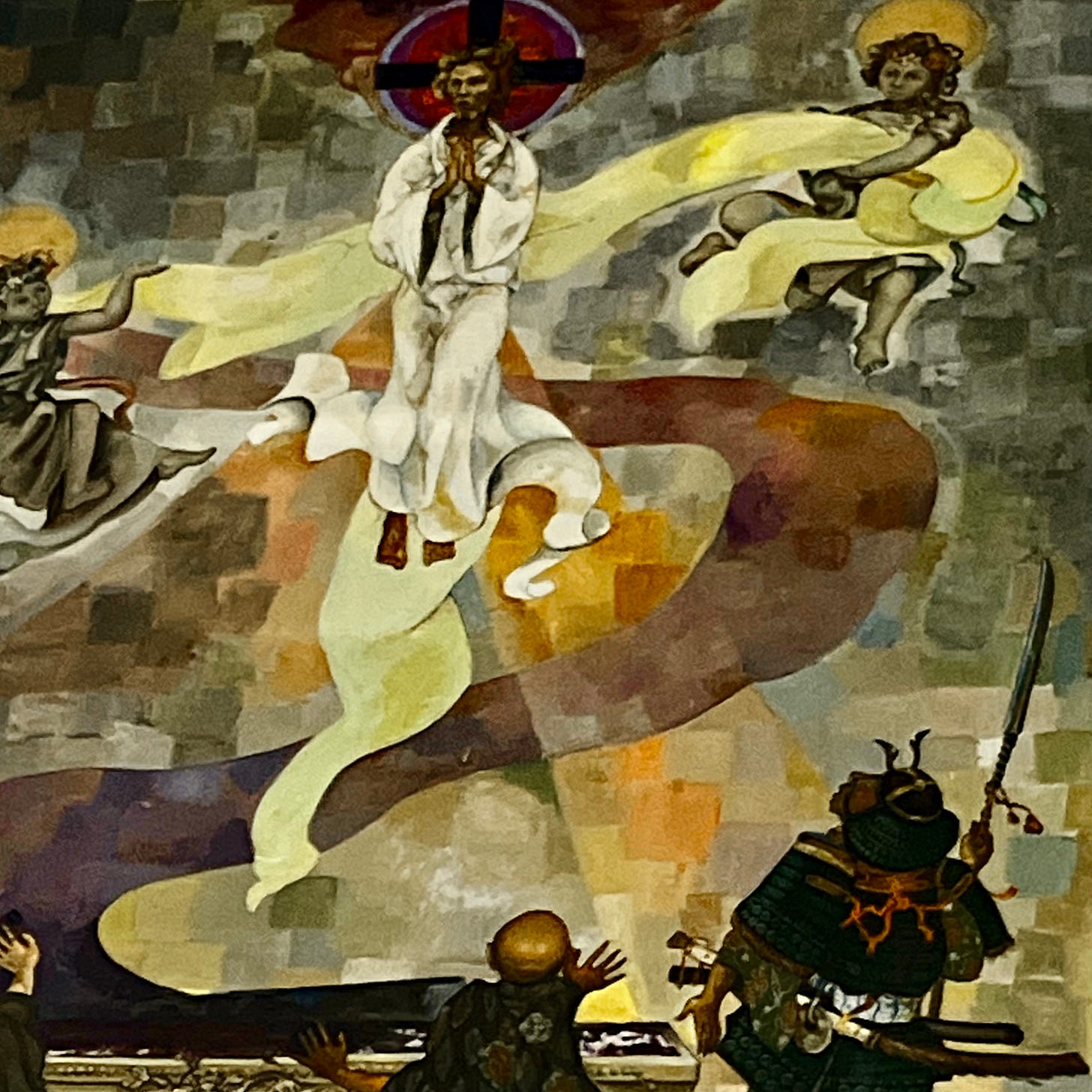

We might recall, though Dionysius does not mention it here, other mountains at this juncture: the mountains of Christ’s Transfiguration and Ascension. Like Christ and His chosen Apostles, Moses here goes not alone up the mountain, but is accompanied by select priests. The three who witnessed Christ’s Transfiguration are left looking at the ordinary man who had, for a moment, revealed Himself as the place of God’s effulgent glory; the witnesses of the Ascension are left gazing up into the cloud where He had been. God is known by his afterburn.

This, I think, is what Dionysius typifies in his next words: the most divine and highest of things that can be “seen and understood by intellect” (tōn horōmenōn kai nooumenōn) are themselves hypothetikoi logoi, “hypothetic forms” (Parker renders them a “suggestive expression”) of all that is subordinate (hypobeblemena, here translated “subject”) to Him who is Beyond All. This, I think, has metaphysical import. Through the hypothetic/underlying logoi, God reveals (deiknutai) His presence (parousia), which is itself beyond all intellection (hyper pasan epinoian). This Presence of God reaches to very highest intelligible/noetic point of His holy places (topoi, this time repeated in the plural). That is, God’s revealed Presence strains to the very limits of existence and hence intelligibility, since for the Platonist, to be is to be intelligible, as He successively reveals Himself through more and more abstract, intelligible Forms or logoi. We strain after Him, through the concrete to the abstract and universal, even through Being and the Good as the most universal and abstract of all, the most common and hence highest forms of reality. But it is only when Moses reaches and strains beyond even these – beyond visible manifestations of God’s presence, beyond the stars and lights, beyond the place beyond places which is God’s abode, beyond heaven, beyond Being, beyond the Good – only then, that he is freed, “unbound” (apoluetai). Though the word epektasis is not used, Gregory’s erotic straining is never far from Dionysian ecstasy.

Freed from what? From both all that can be perceived and from all other perceivers, rising higher even than the angels whom Bartholomew/Nathaniel was blessed to see. There, Moses enters the Cloud of Unknowing, or in Parker’s words, the gloom of Agnōsia. In this Unknowing, a reference again to Acts 17 and the God St Paul proclaimed the Greeks worshipped “through unknowing,” Moses is secreted from (apomuei) all distinctions (antilēpseis) of the discriminating intellect, and enters the “insensible and invisible,” becoming “entirely of the One beyond all things, and not anything,” no longer being “himself or anyone else.” Note again the Pauline reference: “It is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me” (Gal 2:20). Moses is no longer Moses, but one with the self-emptying Christ, a motif to which we shall return.

Dionysius concludes with one of his many compounds of ergon, in this case an-energēsia, or “non-working.” Through the non-working of knowledge, Moses is unified with the utterly Unknown, precisely by “knowing nothing” (tōi mēden ginōskein) – very Socratic! – which is at the same time, “knowing beyond intellect” (hyper noun ginōskein). United with Christ, the Divine Logos, the Much and the Least, the Body joins the Head in the wordless contemplation of the transcendent, unbegotten Thearchy from whom the Word proceeds.

Read the next instalment:

Mystical Theology II: “Hymning”

“We pray that we might approach this super-luminous darkness, and that through unseeing we may see that which is beyond vision, and through unknowing know that which is beyond knowing, by the very act of not seeing and not knowing respectively — for this is actual seeing and knowing — and that we may

Denys always has intresting passages thanks for sharing