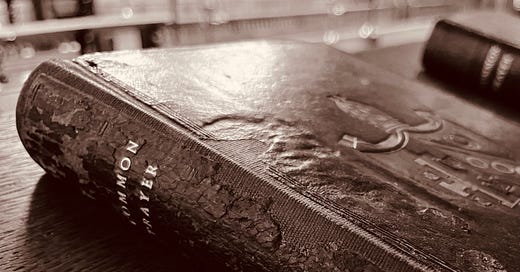

The Church of England’s 1662 Book of Common Prayer has been praised for its elegance and influence on the English language by men and women of letters such as T.S. Eliot, C.S. Lewis, Dorothy L. Sayers, John Betjeman, P.D. James and Sir Roger Scruton. Many commonplace English phrases derive directly from it and that other great work of the English literary canon, the King James Bible. When alternative, more modern orders of prayer began to emerge in the 1980s, many literary voices objected. The new language, they said, was less memorable than the old and would erode the Christian inheritance of the nation; liturgy made by committee lacked the delicate command of rhythm and cadence that the authors and emenders of the old Prayer Book were able to impart; the new rites would soon sound dated, where the Prayer Book, which had remained in constant use for over four centuries, was an undoubted and enduring classic. Much of what they said has proven true, and the Prayer Book is enjoying a revival among young and new Christians, as are the traditional Latin mass of the Roman Catholic Church and the ancient Orthodox Divine Liturgy. Tradition and beauty are back in vogue.

However, there is more to the Prayer Book than its language, and that “more” has not always been welcome. When the first Book of Common Prayer was published in 1549 it received a decidedly mixed response. In Protestant lore, the story of the English Reformation is often told as one of emancipation: the ignorant peasantry, unable to understand the Latin liturgy of the Catholic Church, were finally given the Bible and services in their own language, and liberated from the clericalism and veniality of a hierarchical church. This is, at best, a distortion of the truth. Parish church records showing the gifts that people made for the adornment of their churches suggest that they were really quite happy with their religion as it was.

Regarding the language of the Prayer Book, there is surely some truth in Archbishop Cranmer’s claim:

“Whereas s. Paule would have suche language spoken to the people in the churche, as they mighte understande and have profite by hearyng the same; the service in this Churche of England (these many yeares) hath been read in Latin to the people, whiche they understoode not; so that they have heard with theyr eares onely; and their hartes, spirite, and minde, have not been edified thereby.”

That said, mediaeval prayer books and missals annotated in English for private use and the inclusion of Latin phrases in popular folk songs suggest that the people understood rather more of the Latin liturgy than moderns have credited them. There also remains the uncomfortable fact that for the peasants who could not read, the replacement of their pictures, statues and mystery plays with a Bible, a Prayer Book and a board inscribed with the Ten Commandments hardly served to deepen their familiarity with the faith. Nor for much of Britain was the English of the books they received their native tongue: to the Welsh and Cornish, in particular, Latin was far more familiar. The English Reformation did improve the literacy of the people, but it is hard to deny that it was a top-down movement imposed by the King and his cadre of scholarly clerics. “Grass roots” it was not.

And yet, for all some Cornish detractors dismissed its rites as redolent of “parlour games,” the 1549 Book of Common Prayer was a fairly conservative translation of ancient liturgical texts into English. The rationale for its composition is spelt out in the Preface. It is not only a matter of language, though that was important. The Orthodox churches of the East have always offered their worship in a language the people of their nations can more or less understand, even if in somewhat archaic versions. There was little reason for the Western Church to persist in functioning exclusively in what was, for Englishmen of the 16th century, an ancient and foreign tongue. We can see nowadays the advantages of the Roman Catholic Church sticking with Latin, as it means that wherever one goes in the world, the same rite can be enjoyed by all the faithful. Until Rome permitted services in vernacular languages in the 1960s, this gave Roman Catholics a powerful sense of the unity which Christ exhorted to His Church. However, we should remember that in the 16th century, the Catholic Church was not using a single rite in every country. There were many variations depending on locality or religious order. The liturgies of the Western Church, although they were all in Latin, were far more diverse than they are now. Even in England alone, there were different local “uses.” One of these was the use of Salisbury, or in Latin, “Sarum.” It was different in certain respects from the Roman use, but also from the use in York. Anywhere one went, one would have to learn new rites and would need a panoply of different books. To get through a day’s services, one might need the daily office book to mark the hours of the day, a missal for mass, a sanctorale for the memorial of the saint of the day, a Psalter for one psalms, a hymnal, and if required, another book for ordinations, baptisms, weddings and so on. Part of the purpose of the Book of Common Prayer was to strip this all down into a single use for the whole nation, which could be contained in a single book. Ideally, all that one would need anywhere in the land to offer or join the services of the Church would be a Prayer Book and a Bible. Eventually, these would be supplemented also with a hymnal.

The genius of the Prayer Book tradition was that it took the complex and varied services of the clergy and put them into the hands of the entire people. One of the great tragedies of Henry VIII’s rule was the dissolution of the monasteries, a polite way of saying that he ransacked the land’s ancient houses of prayer for the sake of funding his military ambitions and giving land to his lackeys. But one of the nobler aspects of the Prayer Book was its attempt, however flawed, to make every English parish and home a kind of mini-monastery. Hence, the Book of Common Prayer begins with the Kalendar (yes, with a “K”), which indicates the feast and fast days of the Church, followed by the orders for Morning and Evening Prayer (often called Mattins, with two “t”s in English, and Evensong) . If you have ever been to a modern Roman Catholic service of the Daily Office, you will notice that it is considerably shorter than its Anglican equivalent. This is because Archbishop Cranmer, the compiler of the first Prayer Book, merged together the two monastic morning services of Matins and Lauds into one, and similarly formed Evening Prayer from the two offices of Vespers and Compline, or Night Prayer. The priest in charge of every church in England was, and remains to this day, legally bound to ring the bell every morning and evening to signal when these two offices are sung or said. Cranmer seemed to envisage the people hearing the bell and plodding into church from the fields, or joining in at home. He meant to turn the entire nation, through its network of parishes, into one great commonwealth of prayer, sustained by the communal reading of Scripture in due season as preparation for receiving the Sacraments. Hence the offices of Evensong and, until recent decades, Mattins have been a particular charism of Anglican churches, offered as public worship more frequently than in either the Roman Catholic or Orthodox churches. When the Prayer Book office is observed fully, Anglicans can justly boast that they observe the hours and read more Scripture collectively than any other Christian body. The entire Psalter is prayed every month and the entire Bible read every year. This was no innovation, but a return to the practice which Cranmer found described in the Church Fathers of old.

The Daily Office is followed by the seasonal prayers known as Collects, because they are used in every Prayer Book service to “collect,” or conclude, the prayers of the people in a way which reflects the scriptural readings appointed for the celebration of Holy Communion each Sunday and feast day. For Christians coming from non-liturgical Protestant backgrounds, these Collects give the first taste in the Prayer Book of material drawn from outside the Bible. Nonetheless, neither the Collects themselves nor the order in which Scripture is appointed to be read, which we call the “lectionary,” were Cranmer’s innovations. Both draw deep on the wellsprings of holy tradition. Almost all of the Collects are translations from ancient liturgical sources, as inherited in the old English rites of Salisbury. Many go back as far as the Fathers of the sixth century. The lectionary is based on that of the 4th-century St Jerome, who produced the translation of the Bible into Latin called the Vulgate, still in use today. The order of the readings is not arbitrary, but as it passes through the year of Christian festivals, forms the listening congregation according to an ancient spiritual pattern: purification by repentance and absolution, illumination by the Holy Spirit and perfection by union with Christ. Until the 1960s, most of Western Christendom, including Rome and the Lutherans, followed an almost identical lectionary, which persists still in the traditional Latin mass. However, most Roman Catholic, Anglican and Protestant churches now share a new three-year cycle of readings. This has the advantage of introducing a greater range of Scripture to congregants whose only contact with the Bible is at the Sunday morning Eucharist, though this might seem a rather defeatist attitude. The Book of Common Prayer’s lectionary, on the other hand, repeats the readings on just a one-year cycle, allowing them to permeate the memory more effectively. This and the spiritual significance of the ancient cycle are attracting the notice of a younger generation of Anglican clergy. There is also a certain irony in the fact that Anglicans using the Prayer Book are perpetuating a tradition which endured in the West for 1500 years before being abandoned by the Vatican. It deserves to be revisited.

The next part of the Prayer Book, right at its centre, is the Order for Holy Communion, also called the Eucharist or Mass. This replaced the stand-alone Missal, the mass-book of old. The reason for its postponement in the order of contents is not to suggest any lack of importance, but is eminently practical: it needs to be in the middle of the book to stop the pages from closing themselves when it is being used to celebrate the rite! Its central positioning also suggests the centrality of the Eucharist to the Christian tradition. For on the very night before Christ gave His life on the Cross, His final mandate – which is the origin of the phrase “Maundy Thursday” – was that the disciples “love one another” and “do this in remembrance of me.” Our Lord’s dying wish was that the faithful continue to share in His Body and Blood through bread and wine. Hence this is the chief of all sacraments, the wellspring of the Christian life and the great treasure of the Church.

Baptism is the gateway to the Sacrament of the Eucharist, and so the Prayer Book continues with this principal sacrament of Christian initiation, followed by the order of Confirmation and the preparatory catechism for it. The rites of Holy Matrimony, the Visitation of the Sick, which includes a rite of individual Confession and Absolution of sins and Communion to the dying, and finally the funeral rite follow. These more or less replace the mediaeval books of the Sacramentale, which, as the name suggests, gave the rites for each of the sacraments.

The Prayer Book formally ends with the entire Psalter, the biblical book of Psalms, in the unrivalled translation of Miles Coverdale. However, a collection of miscellaneous prayers, the Ordinal and the 39 Articles are commonly appended to it and printed in the same volume. The precise contents have changed over the ages, at various stages including prayers for the memorial of the martyr King Charles I, remembrance of the Great Fire of London, and the order for consecrating church buildings. Notably, these were removed not at the behest of the Church, but at the whim of Victorian publishers. Nowadays, the miscellaneous prayers tend to include only the Forms of Prayer for Use at Sea and prayers for the monarch on the anniversary his or her accession to the throne. Important as these miscellanea are, however, the Ordinal is more fundamentally a key part of Anglican tradition. It preserves the ancient threefold ministry of Bishop, Priest and Deacon inherited from the early church and held in common with the Roman Catholic, Orthodox and some Lutheran churches.

The Book of Common Prayer of 1549 collated and distilled the wisdom of the ancient church in a manner suited to English-speaking people. Its form was innovative, but its content was ancient. However, the Prayer Book tradition did not crystallise at this point. Some may wish it had, since the subsequent edition of 1552, published under the reign of the Protestant King Edward, moved it in a more radically Reformed direction. By this time, Cranmer was more strongly influenced by the Protestant movements of Europe. Invocation of the saints and prayers for the dead were among the casualties, and the Eucharistic rite was re-ordered to conform more closely to contemporary Calvinist ideas.

Edward’s Prayer Book remained in use for only eight months, too short for it even to be ratified by the church. When he died at the age of 15 and was succeeded by the Catholic Queen Mary, many of the people were happy to see the new prayer books burned and the Roman Catholic services restored. They were less happy, though, when Mary burned Protestant people along with their books: at least 300 men and women in all. On 21 March 1556, in Oxford, Archbishop Cranmer was one of them. But the Book of Common Prayer did not die with him. Mary’s reign lasted only five years, and her successor, Queen Elizabeth I, revived his work, ordering a revised edition be published in 1559. She wanted an English church in which those of Protestant and Catholic positions could worship and work together. She was not entirely successful in this, and she ruthlessly persecuted Catholics who would not submit to her authority. More faithful people were burned, and Good Queen Bess’s hands were not clean of blood. And yet, through the Book of Common Prayer, she did manage to contain some of the disagreements and arguments between Christians and keep the English church as more or less one. Nor did her more traditional celebrations of the liturgy please more advanced Protestants. As one contemporary complained in 1560:

“What can I hope, when three of our lately appointed bishops are to officiate at the Table of the Lord, one as priest, another as a deacon, and a third as subdeacon, before the image of the crucifix, or at least not far from it, with candles, and habited with the golden vestments of the papacy; and are thus to celebrate the Lord’s Supper without any sermon?”

As well as the traditional apostolic order of the Church, Elizabeth was keen to preserve the traditional vesture and liturgical trappings hallowed by antiquity. These were defined in the 1559 Prayer Book’s so-called “Ornaments Rubric” thus:

“Such ornaments of the Church, and of the ministers thereof, at all times of their ministration, shall be retained, and be in use, as were in this Church of England by the authority of Parliament, in the second year of the reign of King Edward the Sixth.”

However, it was only after the execution of King Charles I, the complete ban on the Prayer Book and exile of the Bishops under Oliver Cromwell, and the restoration of the monarchy that the Book of Common Prayer took its current form. The next major edition of the Book of Common Prayer would come one hundred years later. King Charles had been under pressure from Puritans in Parliament to take the Reformation much further. The Puritans thought that the Reformation had not gone far enough, and the Prayer Book was “too Catholic.” They wanted him to abandon much of the ancient tradition contained therein, such as the Kalendar of saints and making of the Sign of the Cross. Especially, though, they wanted the King to abolish the Episcopate, the ancient order of Bishops. He refused, preferring to die than to abolish the living connection to the Apostles. Whatever one may think of the rest of his reign, Anglicans can at least thank him for this. Civil war ensued and, on 30 January 1649, the King was executed.

For eleven years, the country was ruled as a republic by extreme Protestant Puritans. Oliver Cromwell served as Lord Protector from 1652 to 1658. Kings, bishops, dancing and even Christmas celebrations were banned, and the Prayer Book was banned with them. One can understand why public opinion swung against the Puritans. So, when the monarchy was restored in 1660 under Charles II, the Prayer Book was restored to use. However, King Charles II needed to keep peace with the Puritans, and so called a conference between their clergy and the newly restored bishops to discuss a new edition. Very few of the Puritans’ objections were upheld, and the bishops managed to make some changes which took the Prayer Book somewhat closer to its original, more Catholic 1549 form. As they replied to Puritan objections at the time:

“‘It was the wisdom of our Reformers to draw up such a Liturgy as neither Romanist nor Protestant could justly except against. For preserving of the Churches’ peace we know no better or efficacious way than our set Liturgy … when the Liturgy was duly observed, we lived in peace; since that was laid aside there hath been as many modes and fashions of public worship as fancies. … If we do not observe that golden rule of the venerable Council of Nice, ‘Let ancient customs prevail,’ till reason plainly requires the contrary, we shall give offence to sober Christians by a causeless departure from Catholic usage.”

Among other returns to tradition, the word “minister” was replaced with “priest” throughout the Prayer Book, an explicitly Catholic exhortation to Holy Communion was added, the commemoration of the departed was restored, the traditional priestly gestures in the Eucharistic prayer called “manual acts” were formally indicated in the rubrics, a rubric formally requiring that clergy reverently consume of any remaining bread and wine was added to ensure that the real presence of Christ in the Sacrament was not violated in any way, and, perhaps adding salt to the Puritans’ wounds, a declamation against “schism and rebellion” was added to the prayers of the Litany recited three times a week after Morning Prayer. Even though the Common Worship series published first in 2000 is in reality far more widely used today than its venerable forebear, is officially only an optional alternative, and the 1662 Book of Common Prayer, formed in the crucible of revolution and restoration, remains legally normative in the Church of England today.

The Prayer Book in all its forms has inspired both admiration and contempt according to the persuasions of its observers. In 1549, it was seen by many as a radical departure from the Catholic faith of old. Just over one hundred years later, in 1662, it had become a symbol of the continuity, tradition and Catholicity of the English Church. The prayer book of 1552 was despised by those of Catholic sympathies, that of 1662 by the Puritans. By the dawn of the nineteenth century, the pendulum had swung again, and many of the symbolic trappings now associated with Anglican churches throughout the world, such as choral music, ornate churches, vestments, even candles and crosses had been suppressed to the extent that their use was now illegal. The Church of England at this stage was barely differentiable in outward form from the Protestant churches of the Continent. And yet, as a band of scholars and priests centred in Oxford discovered, the theology of the Book of Common Prayer was closer to that of the ancient Church Fathers they were studying than the modern-minded generation before them had supposed. John Henry Newman, John Keble and Edward Bouvery Pusey were among those to maintain that the Book of Common Prayer was consistent with the Catholic faith of the ancient Church. The Oxford Movement which they started in 1833 at first was purely doctrinal, and made no attempts at changing the outward form of the liturgy they offered. However, it became clearer that the outward form of the liturgy had, could and should represent the theological commitments behind it. The Elizabethan Ornaments Rubric was used to justify the restoration of candles, incense, vestments and crosses in worship. Not, however, without a cost. In 1844 the Surplice Riots began in Exeter, where the people resented the imposition even of what seems to us today an innocent and quintessentially Anglican garment. In the 1860s, priests were imprisoned by the civil authorities for using wafer bread instead of loaves and for lighting candles on the altar during Holy Communion. Clergy and people processing the Blessed Sacrament through their London slum parishes had the contents of their neighbours’ chamber pots thrown at them, and even in one case a dead cat.

By the turn of the 20th century, the Oxford Movement was in the ascendent to such an extent that the laws against what were now called Anglo-Catholic practice were largely ignored. Legal solutions to liturgical and ritual differences in the Established Church attracted widespread distaste. Hence, in 1906, a Royal Commission on Ecclesiastic Discipline recommended revision of the 1662 Book of Common Prayer to reflect the contemporary situation of the church. More pressing priorities came to the fore, however, as the world began to move towards the Great War of 1914-18. This, too, had an effect on the religious temperament of the English people. The Oxford Movement had awakened in the people a desire for more frequent reception of the Blessed Sacrament of the Body and Blood of Christ, especially immediately before death, as the Prayer Book rite for the sick had always exhorted and stipulated, but celebrating an entire rite of Holy Communion in the trenches for every wounded soldier was entirely impractical. The recipient was liable to die before the service ended. The Sacrament needed to be reserved from a previous celebration and taken to the sick and dying. This, however, was a controversial point for those of more Protestant belief, who had opposed the Anglo-Catholics’ veneration of Christ in the Sacrament. There was also a renewed need for requiem masses and more broadly for those who had died overseas, a practice which many Protestants consider unbiblical. These pastoral needs drove more and more Anglicans into the Oxford Movement’s camp, to the extent that attendance at the national Anglo-Catholic Congress in London rose from 13,000 in 1920 to 70,000 in 1933: a figure of attendance almost unimaginable now, but something to be aspired to.

Delayed by the War, only in 1927 did the church complete the promised Prayer Book revision begun in 1906. Faced with the experience of the returning wartime chaplains and the pastoral needs of the people, the reforms moved in a far more Catholic direction, more closely reshaping the Eucharistic rite to the 1549 shape, with some influence from the Scottish liturgy. Even within the church, the Deposited Book, as it was called, did not please everybody: for while those on the Reformed side were perturbed that the Kalendar was expanded with a greater number of memorials of saints and reservation of the Sacrament was permitted for the sick, Anglo-Catholics were affronted to find that eucharistic devotions such as Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament were to be firmly proscribed. Yet the church’s differences proved to be of little account in the end. For even though the Convocations of Canterbury and York approved the new Prayer Book and submitted it to Parliament, while the House of Lords passed it, it was defeated in the Commons. The irony that the Church of England’s liturgy and doctrine were being debated and decided by a state body which included large numbers of nonconformists was not lost on the Chancellor the Exchequer, one Winston Churchill, who described “the greatest surviving Protestant institution in the world patiently listening to debates on its spiritual doctrine by twentieth century democratically-elected politicians who … have really no credentials except goodwill. It is a strange spectacle, and rather repellent.”

Although the 1928 Book of Common Prayer was never approved in Parliament, leaving the 1662 edition as the official liturgy of the Church of England to this day, in practice the bishops found a workaround, appealing to their ancient jus liturgicum by which any bishop bears ultimate responsibility for the rites permitted in his See. Only four out of the twenty-seven bishops of the time refused, in the formulation proposed by the Archbishop of Canterbury, to “regard as inconsistent with loyalty to the principles of the Church of England the use of such additions or deviations as fall within the limits” of the Deposited Book. The path was laid for reasonable interpretation of the liturgy within the bounds of the wider Prayer Book tradition. Exactly how much lassitude there is in those bounds remains a pertinent question, and one which has arguably led to some of the more experimental liturgical practices in the Church of England today. These range from Charismatic band-led praise services to liberals’ homemade liturgies on environmental or social justice themes, and bear little if any resemblance to the tradition inherited by the Church of England. However, what is sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander, and the same lassitude has allowed Anglo-Catholics parishes to introduce services of Eucharistic adoration. In some, in place of the Church of England rites, the Roman rite is used in its entirety, on the basis that the modern Common Worship liturgy allows such flexibility and use of alternative translations that one can legitimately claim that the Roman rite is a “permissible variation.” Some bishops, particularly in the Society of St Wilfred and St Hilda, also exercise their jus liturgicum to permit Roman usage in their Sees. Nonetheless, the Book of Common Prayer remains the normative liturgy of the Church of England, and its study is of value to every Anglican Christian, whether or not it is used in one’s own parish.

The history of the Book of Common Prayer raises questions about the proper relationship between the Church and the state. It seems wrong that non-Anglicans were able to outvote the Church of England on revisions to her own liturgy. Nowadays, the Church enjoys greater freedom in this respect. Whether the church should remain established or not is a vexed question within the Church of England, especially given the recent pressure from government ministers on the church to revise its position on same-sex marriage and the potential schism that now confronts the church on this issue. Disestablishment would surely be a better option than allowing Parliament to push the church into heterodox innovations. Nonetheless, the normative legal status of the Book of Common Prayer for now, at least, offers a safeguard to the tradition of the undivided, Holy Catholic Church of which our church claims to remain a part.

As well as the various editions of the Prayer Book in England, and the permissible lassitude in its interpretation, there are many other Books of Common Prayer in Anglican churches overseas. Unlike the churches in communion with Rome, whose largely unified liturgy represents the centralised authority of the Papacy, the daughter churches of the Church of England are a communion of autonomous churches competent to authorise their own liturgies within the bounds of Scriptural, creedal and conciliar authority. Hence the Prayer Books of Scotland, America, Japan or South Africa, for instance, differ. Some offer rites closer to the ancient Catholic sources, others are more markedly Reformed. All, however, are recognisably continuous with the Prayer Book tradition of 1549. Rather than Prayer Book fundamentalism, then, it is perhaps better to think of the Prayer Book tradition in a broader sense, as the lex orandi, the rule of prayer, which forms the lex credendi, the rule of faith inherited from the Apostles.

There is much talk among “intentional communities” of Christians about discovering a spiritual rule of life. Many adapt existing monastic rules, mostly the Benedictine, to the demands of secular life. This is all commendable. However, one resource is too often overlooked. The Book of Common Prayer itself, with the pattern of its Church Kalendar, the days and seasons of Eucharistic feast and penitential fast, the hallowing of the hours by Mattins and Evensong, the ordering of one’s life by the pastoral offices for childbirth, marriage, healing, and commendation of the dead, offers a robust rule of life which for centuries has guided English-speaking Christians to holiness, and to likeness and union with their Lord. It is a fine repository of the Apostolic tradition which, when followed consistently and thoroughly, can yet yield great spiritual fruits.

If you enjoyed this article, you may also like these:

The Prayer Book and the Culture Wars

Only in my mid-twenties did I realise that I had been brought up to believe in some strange things. I was inculcated throughout my youth with outlandish and undemonstrable doctrines, dogmatically asserted by authority figures and reinforced by the approval of my peers. Anyone bold enough to venture criticism or a rival position was quickly ridiculed int…

I have been reading Fr Martin Thornton’s work lately and I appreciate the good historical work you have done to help contextualize his positions on the Prayer Book “Regula.” What prayer book do you most frequently use?

I have mixed feelings about the venerable Prayer-Book, even though I hold great respect for it. I simply feel it eliminated too much — the Offices, which everywhere else were services offering praise to God, evening and morning, were converted into a vehicle principally designed for the reading of Scripture (without, unlike in the old ritual, interpretation from various Fathers). I've prayed both the 1662 ritual and the Benedictine Office in Anglo-Catholic translation, and the difference is stark; it's not so much a condensation or reformation as an entirely new liturgy with motifs from the old. (For the lay-person, this might not be too poor of an idea — Matins in the old ritual is truly titanic on Sundays!). On the other hand, it really does allow for one to interact with a large amount of Scripture and a reasonable number of Psalms daily... I just wish that it maintained more of the older ethos.

The Eucharistic service also concerns me, because it really does seem to imply a receptionist view. I understand many Anglo-Catholics have been creative in their understanding thereof (cf. Tract 95), but I still feel uncomfortable with the structure of the 1662; I think Dom Dix was right when he notes that this liturgy is the only one that truly embodies the doctrine of justification by faith alone.

I think the Prayer-Book is beautiful (I exclusively pray the Coverdale Psalter); it is just too Reformed for me! I've looked at the earlier revisions, and I'm certainly more amenable to the pre-Edwardian edition, but nevertheless.