Morello's Option: Counter-enchantment

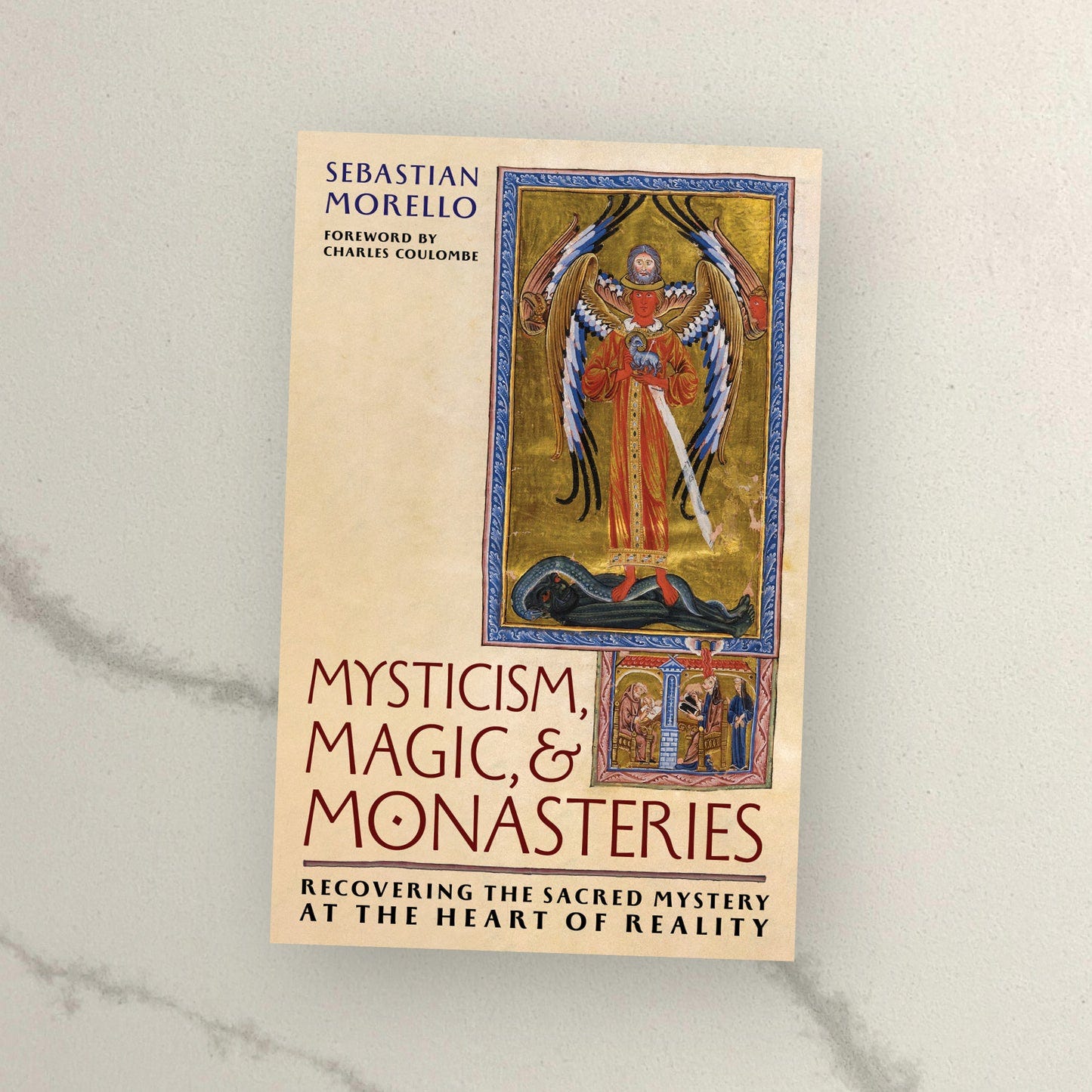

Book review: Sebastian Morello, "Mysticism, Magic and Monasteries"

Many, myself included, make breezy demands for "re-enchantment," but what exactly does this mean? Morello's pleasingly uneven new book weaves theological reasoning with anecdote both illuminating and entertaining to throw light on the question. Although his analysis ranges widely across topics, it at least casts largely internet-driven conversations about "enchantment" into clearer definition.

Morello's thesis is twofold. First, the Christian searching for re-enchantment should do so literally, by way of magic: namely, the sacramental life of the Church, understood as a kind of theurgic counter-spell against the betwitchment of modernity. Such Christian theurgy, claims Morello, is most explicitly found in the Hermetic teachings which informed certain apogees of Renaissance Catholic thought. Secondly, the desired magical thinking can be achieved only by the restoration of monastic communities, as the foremost Western exemplars of the theurgic, sacramental life he espouses: not a new Benedict "option," Morello stresses, but the old Benedict redivivus.

In the way of this noble quest stand various enemies. Chief among them is Descartes and the mind-body dualism which, Morello opines, underpins modern materialism. Descartes stands in a genealogy of antagonists fathered by Ockham and mendicant orders in general, though notably in contrast with standard genealogies of Dreher and Radical Orthodoxy, the author does not number Scotus among them. Their ill seed extends through the Reformation, then via Ignatius of Loyola and Descartes, to twentieth-century proponents of the Nouvelle Théologie, whose theological contributions to the Second Vatican Council modernised and so, Morello thinks, Protestantised the Church, finally exorcising her of her last breath of magic.

The new mediaeval mendicant orders of Ss Francis and Dominic destabilised the old Benedictine monastic order, grounded in broadly Platonic spirituality; Ockham's nominalism was the inevitable result of extended detachment from this older way; the ensuing division of mind from matter inspired St Ignatius to develop a psychologising and individualistic spirituality, perpetuated by theologians of the Nouvelle Théologie, especially the Kantian Karl Rahner SJ, the evolutionary Pierre Teilhard de Chardin SJ, and Hans Urs von Balthasar, who invites the author's particular distaste. All are trapped in a Cartesian worldview.

One might sympathise with Morello's diagnosis of modernity as an "egregore," a bewitchment of the mind, and with the solutions of sacramentalism and monastic asceticism. Fr Hans Boersma might go that far. The assertion that Christian Hermeticism is the necessary or even best vehicle to this end, its alleged connection to Benedictine spirituality, and the dismissal of both Protestantism and the Nouvelle Théologie tout court as "modernist" are, however, less obvious. The real progenitor of the latter movement, Henri de Lubac, despite being yet another Jesuit, escapes Morello's ire and even mention—perhaps because the accusations made against him, in his lifetime, of "modernism" were roundly defeated. A proponent of Ressourcement, he called for a return ad fontes, beyond the narrow Scholasticism of the contemporary church towards a supernaturalist view with which one might imagine Morello sympathetic. Though Morello may blame de Lubac for leading the Nouvelle Théologie's rejection of the Thomistic possibility of pure, ungraced nature, to suggest that the Cardinal in some way naturalises the supernatural, while a reasonable charge to make against Rahner, is the position de Lubac opposes and rejects in his Surnaturel.

That this supposed elision of nature and grace is typical of Protestantism (viz modern and bad) is something against which Richard Hooker, Lancelot Andrewes, Thomas Traherne, the Cambridge Platonists, Pusey, and the Anglicans among the Inklings might have objected, since they taught a Neoplatonic, sacramental Christianity as robust as anything on the Continent. Indeed, if one were looking for something more exotic, Richard Yoder has demonstrated that there were many Anglican members of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn founded in 1887, priests and Benedictine monks among them. Some even shared Morello's fear of the Jesuits.

Magic

One has to wait until chapters 4 and 5 before the author begins to treat specifically of Hermetic magic. The Protestant-Jesuit nexus duly despatched, he offers as champion of the better, Platonic and Hermetic way Valentin Tomberg, who anonymously published his Meditations on the Tarot in 1967. This impressive and eclectic tome of Christian occultism numbered among its admirers, to Morello's chagrin, the ex-Jesuit von Balthasar, who wrote its foreword. But to compare the Meditations to the work of the Nouvelle Théologie is much like comparing its source material, the Hermetic Corpus, to the works of Plotinus. Not that Morello has space to do much of this in the two brief chapters.

One is left with little knowledge of quite what the Hermetic Corpus is, or what Tomberg makes of it, beyond the principles of "as above, so below," and the vision of the "world as icon." One could find these principles better expressed, under sharper scrutiny, in other Platonic sources, ancient or modern. The authority of the Hermetic Corpus in pagan Platonic circles was its basis in supposed revelation of the Egyptian God Thoth under his Greek name Hermes Trismegistus; the later Chaldean Oracles are based on a similar claim of divine revelation, and were deployed for this reason by later Platonists, notably Iamblichus and Proclus, as a means of reinforcing Platonic philosophy against the onslaught of popular Christian piety. Were one to seek an intellectual grounding for theurgy, that practice of sympathetic magic which St Dionysius baptises into Christian sacramental theology, one could turn to either of these late great Platonists without turning to either of the more Stoic-Platonic hybrids of reputed revelation. This Iamblichean-Proclean strand of Neoplatonism is where Pico de Mirandola and Marcello Ficino, two of Morello's heroes of the Italian Renaissance, turned. A preference for these more credible and tested sources would better support Morello's argument. Instead, perhaps inevitably in a book which combines brevity with such scope, the character of the protagonists is left as undeveloped as that of the antagonists; but if it prompts the reader to return to Tomberg's Meditations, perhaps it has served Morello's purpose, and the diatribe can be enjoyed as controversialism.

Monasticism

Morello's admirable conviction that man is a liturgical animal, grounded in a somewhat makeshift exposition of Hermeticism, segues into a defence of Benedictine monasticism. Here, Morello parries with various contemporary commentators, most of whom are denizens of the online Christian and Christian-adjacent "spiritual right": Paul Kingsnorth, Rod Dreher, John Vervaeke, and Iain McGilchrist all appear. This shows where most of his conversations are happening, an impression reinforced by the inclusion of two eclectic appendices: correspondence with Peer Kwasnieski on Holy Orders and Matrimony, and a review of Rod Dreher's Living in Wonder. There is therefore a certain irony, not unappreciated by Morello himself, in his observation that Catholicism has become "an internet phenomenon." This results from the absence of what he deems a faithful hierarchy since Vatican II, which has hollowed out the liturgical and spiritual heart of Catholicism in which true doctrine is grounded, leaving Catholics stranded in the Protestant-Cartesian-Jesuit realm of ideas and argument.

Only monastic renewal, says Morello, can offer the remedy for modernity's life of abstraction and the possibility of a life fully liturgical. However, his choice of interlocutors suggests that he is as much a part of the ether as anyone, and his polemic sometimes bears signs of internet zero-sum "owning" strategies. He does not hesitate to call out others on that charge, even Paul Kingsnorth, arguing that Benedictine monasticism is just the "wild and weird" kind of Christianity that the Orthodox convert thinks has been extinguished in the Western Church. He also challenges Kingsnorth's animus "Against Christian civilisation," most famously expressed in the First Things article of that name, arguing instead that, paradoxically, the Benedictines were the necessary and desirable grounds of that civilisation historically, and could be so again. The West needs no new Benedict, he insists, but the old one.

Mysticism

In discussing mysticism, we find perhaps the least resolved conflict in this book: the author's purported resistance to perennialism versus his commitment to Hermetic or broadly Platonic tradition. Perennialism, he wrily and rightly notes, tends to lead to Islam, specifically Sufism. His solution, it seems, is to pitch Christianity as a theology of incarnational and ecclesially channelled grace against a pagan notion of an already graced cosmos; hence he rejects the Orthodox essence-energy distinction, which he thinks leads Dreher into pantheism.

And yet it was the sundering of grace from St Thomas's hypothetical natura pura that led to the ultra-Augustinianism of Calvin and the binary of Reformation solas. The Weberian "Protestant work ethic" depends on the notion that matter is ungraced and that its value is ultimately definable by utility to man, hence subjecting it to the author's despised "price tag." It is against this that de Lubac rallied Greek patristic sources.

My own reading of the Christian Platonist par excellence, St Dionysius the Areopagite, who bridged the worlds of pagan and Christian philosophy, suggests a less clear divide between the two than Morello desires. Fr Andrew Louth is among those who maintain that despite importing extended passages of Proclus verbatim, Dionysius is himself not in continuity with pagan Platonic precursors, but merely used their terminology in new and equivocal senses. Yet one might make the same argument about any pagan Platonist in respect to his precursors, too. The fact that Proclus may interpret the one in a different way from Plotinus, or Plotinus from Plato, say, does not imply that they are anything but interlocutors and interpreters within one tradition, marked by both continuity and discontinuity: for that movement between minds is surely what a tradition is, rather than a static body of doctrine. One might say too, that Calvin is working demonstrably within the same theological tradition as St Thomas Aquinas, despite considerably different uses of like terms and different conclusions.

The question of where one tradition ends and another begins is similar to when a dialect becomes a language. If the answer is when the two become mutually unintelligible, then I would assert, on an empirical basis which I have tested, that even such remote traditions as Christianity and Buddhism, let alone Catholicism and Protestantism or Christian and Pagan Neoplatonism, are demonstrably dialects of a common tongue: that is, as a good Thomist would aver, they are neither univocal nor equivocal in their use of language, but analogous. It is analogy, a Neoplatonic concept, that makes the sacramental ontology the author desires possible, and casts such serious doubt on the concept of pure nature.

One such analogy can be found in the exhortation of the last chapter of Morello's book, where he proclaims the merits of mace-swinging, a form of physical exercise apparently enjoying a renaissance in conservative male circles. It comprises the recovery (or ressourcement?) of mediaeval combat techniques. Once one has mastered the form sufficiently to combine them, one enters a semi-conscious "mace flow" wherein one is instinctively guided by the weapon, rather than making conscious decisions about where to guide it. The same, he notes, applies to Eastern martial arts. But herein hides the analogical principle. My own martial art of Aikido also works by mastering forms only in order to abandon them to a flow of bodily harmony with one's opponent. It clearly has something in common with mediaeval Western mace fighting. Yet Aikido is based explicitly on Buddhist, Shinto and Confucian theological and philosophical principles, as are all of the traditional Japanese arts, martial or otherwise. I recently saw a Japanese calligrapher demonstrate. And where the master took a great brush and emitted a loud ki-ai shout before literally leaping forward to draw, with rapidity, accuracy and flow, her kanji on the paper on the floor. Such arts need no recovery: they are part of a continuous, living tradition, just as the Latin Mass was before the reforms which followed the Second Vatican Council snuffed it out of the collective memory. In my own case, what woke me up to what Morello calls a pre-modern or liturgical mindset was my firsthand experience of the ritualised arts of Japan. I can no more dismiss that culture as diabolical than Morello can dismiss the Hermetic Corpus or Neoplatonic philosophy. The analogy between the Japanese arts and all that we have lost in traditional Christianity and the wider life of the West is all too clear.

This leads to where I differ in my approach to Morello's analysis of "TradCaths" as an internet phenomenon, and likewise to the feisty "Orthobros." Morello suggests that they amount to a commodification of religion as ideological commitment, chosen from among many, rather than as a liturgical life, lived in common. Anyone who has spent time agonising over whether to be Catholic, Orthodox, Reformed or Anglican might find solace in this thought. One can form an opinion about one's ideal church online, then visit to find some nun with a guitar or priest in a polyester chasuble, some ultra-nationalist Russian political cell, or some washed-out rainbow-draped Episcopalian abomination, and find it all wanting. Morello takes easy swings of the mace at Orthodox "Caesaro-papalism" and dismisses the Anglican mess in a single clause, but those of us outside Roman Catholicism have reason to be equally wary of Rome when we see, as the Orthodox do, the power of the wrong Pope to abolish traditional liturgy at the stroke of a pen.

Traditional Reformed and Anglican circles, like traditional Catholic and Orthodox ones, are growing, and we are not memes: we are churches. But where Rome and the non-liturgical Evangelical churches differ from the rest is in their suppression of the local forms of the Christian tradition which were constitutive of Morello's desired pre-modern mindset. The rolling out of identical megachurches, playing the same music, in which people wear the same "plastic coverings" that nowadays, Morello snipes, pass for clothes, echoes the strategies by which Rome pushed for one uncompromisingly uniform rite on the entirety of Western Christendom: and that happened not after Vatican 2, but at Trent. The Protestant churches were not alone in jettisoning tradition; Rome showed the way. And ironically, it is in such liturgies as the Book of Common Prayer that pre-modern Christian tradition specific to the English-speaking peoples is best preserved. King Henry's destruction of the monasteries was a terrible thing, and their restoration in England a cause for great joy; and yet, the Book of Common Prayer gave the English layman a religious life, governed by recitation of the simplified Office, far closer to the Benedictine than the Catholic laity for whom only the mass, and that infrequently, remained. Visiting French clergy even expressed surprise at the Benedictine appearance of the standard English clerical habit. Both Rome and Canterbury have lost much; from one another, they stand to gain. And by analogy, this principle extends wider, far beyond the closed (and basically online) Roman Catholic-Orthodox colloquy in which Morello contends.

I suspect that Orthodox and Anglicans alike might see a certain beam in Morello's eye: the pre-modern localism he rightly exhorts has, for centuries, not just since the 1960s, been precluded by the totalising instincts of the Vatican. Rather than offering a rival to modernity, it offers a rival facet of it, namely monopoly, enabled by technological advances in transport and communications. If we were truly to return to a premodern mindset, we would reject the very idea of religion as a market choice. People of old did not by and large choose Anglicanism or Lutheranism or Orthodoxy or Roman Catholicism. Europeans' religion, like that of the Japanese, was constitutive of their inherited identity as parish and nation. One might legitimately question one's own churches commitments and challenge them (q.v. Laudianism, the Oxford Movement, or Evangelicalism in the Church of England, the New Liturgical Movement in Rome, and nowadays the growing number of expressly liturgical Reformed churches), one would no more readily abandon one's inherited church than one would one's family or nation. In the case of the moribund Church of England, rather than abandoning it for something we have seen on the Internet and like better, is it not better to occupy and restore it?

Caveats aside, the author succeeds in advancing largely internet-driven conversations about "enchantment" towards a stronger definition. Each chapter is a pleasure to read in its own right, and I suspect these may originally have been individual essays put together in a not quite seamless whole. One can enjoy his invective without being too swayed by it; heed his caution about conflating nature and grace without necessarily accepting his diagnosis of the Nouvelle Théologie; and embrace the patristic and Neoplatonic bent while being aware that it is to be found beyond the bounds of either Hermeticism or Rome. Above all, though, we should seek to enter the pre-modern mindset he exhorts, not only by reading about liturgical life, but by finding a local church and living it.

Great piece Father. Yes, most of the chapters in the book appeared as stand alone essays in The European Conservative mainly throughout 2022 and 2023.

I share your views overall. Morello is really astute in his diagnosis of the problem. 'Hex' is a great word, and that's what it is. That's what modernity is in a nutshell. We absolutely need to recover the pre-modern worldview that's open to the Mysteries in ways that we've forgotten or lost these past few centuries.

Your reservations are mine as well though, and I say that as a Roman Catholic and an avid listener of Morello's Gnostalgia podcast. The Roman Church doesn't hold all the aces here in either it's Tridentine or post-conciliar forms. This is where Anglo Catholicism can make a really valuable contribution, I feel. It's style of worship, at it's best, can feel both grounded in the particular and universal in its range and scope. Its aesthetic and overall ambience connect us back to a deep, fertile spirituality that predates the iconoclasm and standardisation of the Reformation and Counter Reformation eras.

A good springboard then for the shift in mindset required to break the hex!

Great review. I’m midway through the book and am finding it inspiring and frustrating in equal measure. Thanks for pinning some of these concerns down in such a clear way.