This year, the rhyme didn’t work. When I came downstairs on the sixth of November, my wife was telling my daughter about the fifth, which I had quite forgotten.

My own childhood memories of Bonfire Night remain fond.Thick coats and balaclavas, wellies and woollen scarves, toffee apples, fireworks, sparklers illumining our white breath in the dark, because November was still cold then. And of course, the burning Guy. I am not old enough to have gone around the streets dragging him on a sled, as my parents’ generation did, but I do remember him sitting in the garden in the days leading up to his immolation, and finding him quite sinister, even before he was set alight. But I went along with it. After all, there were sparklers.

At some point, I must have learnt that Guy Fawkes was a Catholic. While I was born far too late to imbibe the full anti-papist sentiment that his pyres used to ignite, that insight no doubt fuelled my general English Protestant impression of Catholics as superstitious servants of a foreign and authoritarian creed. But in 1980s rural Worcestershire, the anti-papist verses had all been long since dropped from the day’s famous rhyme (though I suspect it may have been rather different in, say, Northern Ireland). I didn’t specifically associate burning the Guy with burning a Catholic: more just an old enemy of the state. The most effective propaganda instilled in my mind from the Bonfire Nights of my childhood is a permanent fear of fireworks, thanks to incessant safety warnings played on TV.

Nowadays I am more circumspect about it all. Though I remain a royalist, and have no truck with political violence, my religious sympathies are far more Catholic than Protestant. I dislike the way that all the old British anti-Catholicism has been legitimised in recent years by child abuse scandals, which are real and horrible, but are at least as prevalent in other dark quarters where journalists seem less willing to shine the light. Even as an Anglican priest, I have received angry men’s misaimed ire when out on the streets in my cassock. I can imagine a growing number of Englishmen for whom not just a Catholic, but any Christian would do as a victim for the pyre. But my fundamental concern, as the range of effigies grows, is that Bonfire Night has become a symbol of people’s ever more rabid craving for scapegoats.

For the English, the traditional scapegoat has been the Catholic. Throughout Europe and Muslim nations, it is the Jew, against whom all the barely hidden nastiness of old is now marching jackbooted back into the light. For the Marxists, it is the bourgeois. For the critical race activists, it is the white man. For the gender activists, it is the heterosexual. For some of the more extreme Greens, it is all of humanity that deserves conflagration. I am wary of all such collective hatreds. They are signs of sickened souls.

The reassembly of these Guys for the pyre has rapidly accelerated in the last few years since Covid struck. Effigies are effaced or thrown into rivers, images defaced in art galleries or torn down from walls. People with the wrong views are cancelled, deprived of work and social standing, driven out of the city. Those who see that the scapegoats look frighteningly like themselves keep quiet, hunch their shoulders, and try not to be noticed. Let the scapegoat bear away their sin of creed or class or race or sex.

The original Israelite scapegoats were sent out to the wilderness alive, and so were not considered sacrifices, though quite how long they would survive I do not know. “Scapegoats” in the modern use of the word, however, cannot be so clearly distinguished from sacrifice. Child sacrifices to Moloch, the sacrifice of Iphigenia to appease Artemis’ wrath and obtain favourable winds, and the offering of produce to stop Raiden from blighting crops with his storms are just a few examples of a universal human practice of appeasement. In times of trouble, whether of natural disaster, war, common plague or sickness, exile is seldom enough to expiate our sin: we look for something or someone to kill and burn. Over the last decade or so, we have experienced all of these on what is approaching global scale. So, we should not be surprised, given the patterns of human history, by the recent surge in scapegoating, and its more recent violent segues into sacrifice.

Much of this is long precedented. However, there is one crucial novelty. Even as late as the last World War, the majority of the world’s powers and peoples held at least formally some sort of supernatural affiliation. The Marxists and, to a lesser extent, the Fascists were the exception to a world that was still religious. Nowadays, the most powerful nations are functionally atheist. Their people are either indifferent or hostile to religion.

The trouble is, the majority of these now functionally atheist countries are those which were once Christian. Why, you might wonder, is this a particular problem, if the need to offer sacrifices is universal? Because the Christian way of answering that need is unique, and until recently, was the defining factor of Western identity and the best export we had to offer the world.

Christianity does not remove the human need for scapegoats or sacrifice. It does not, pace Bonhoeffer et al, remove the need for religion, for religion is literally “what binds,” our obligatory ritual practices of offering. It does not remove the need for animal or even human sacrifice. Rather, it fulfils that need.

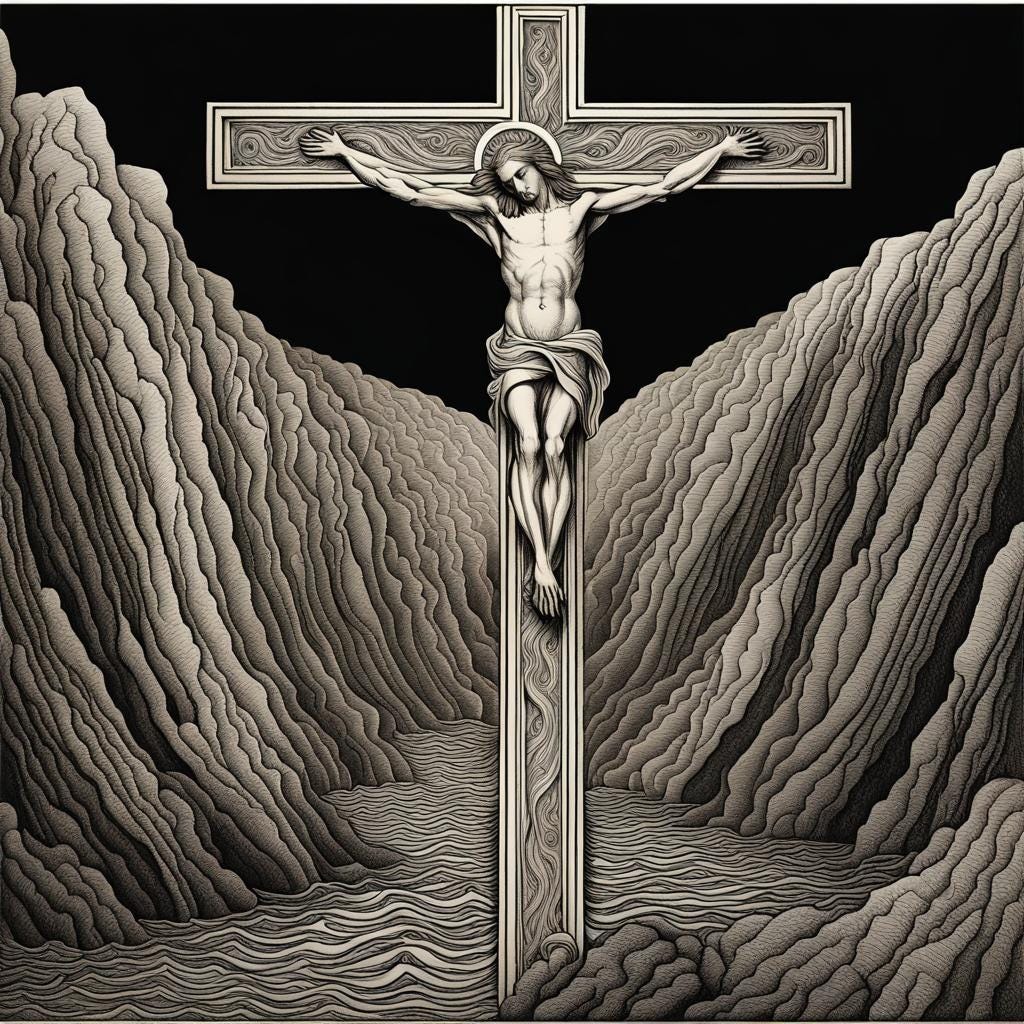

When Christ offered Himself on the Cross, He did not negate but sublimated both the scapegoat and the ritual sacrifice. As scapegoat, He bore the sins of all people. As sacrifice, He was at once both priest and victim: a sacrifice both divine and human. This is one of the reasons why the Romans found His cult perverse. By the time of the early Church, while the Romans were happy to offer animal sacrifices, they found human sacrifice distasteful. Yet here was this Jewish sect meeting in secret, claiming to eat the flesh of a man. Not only human sacrificers, then, but cannibals, too. Even their own scriptures, such as John 6, witnessed against them. And all this perversion they were carrying out instead of offering the proper, respectable, state-mandated sacrifices to the divine Emperor and tutelary deities of Rome. Such blasphemous obstinacy jeopardised the Empire’s divine protection and risked provoking the gods to anger.

The second century apologists St Justin Martyr and Athenagoras denied the charges of atheism and child sacrifice that were levelled against them. Yet neither of them specifically denied the charge of cannibalism. They did not claim only to be reenacting the past event of Christ’s death on the Cross by means of bread and wine. Nor, though, did they claim to be eating His dead flesh, as one would eat the flesh of a slaughtered animal. Rather, Athenagoras said, through the bread and wine they were consuming the living flesh of the heavenly Christ. If Christ had been only human, then indeed, the act of Holy Communion would be perverse indeed. But because He is both human and God, the act is meet and right. His human body has become heavenly food.

This is not just a theological nicety. It lends to two convictions which directly bear on modern scapegoating and the trajectory of world history henceforth.

First is the conviction that in the historical event of the Crucifixion, Christ as Divine Human made an all-sufficient sacrifice for the sins of the world. In so doing, He both proclaimed forgiveness and made it possible, because when we see that our own evil has been paid for, generosity and honesty demand that we see that the same is true of everybody else. When God cancels Himself, there is nothing left for us to cancel. This first conviction was widely held in Christian nations until at least the middle of the last century.

However, there is a second which slipped from memory rather longer ago, but which is essential for the first to be much more than a helpful moral tale: namely, the conviction that the night before He died, as His last commandment, Christ bequeathed to the Apostles a sacrificial ritual to be performed ever after. Jesus’ taking and offering of bread and wine was a preliminary part of the Passover sacrifice of which He was to be the Victim. Already by St Paul’s time, which is to say, before any of the Gospels had even been fully compiled, the faithful who approached the Lord’s Supper were to do so worthily, and were to partake of Communion only if they recognised Christ’s body and blood in the bread and in the cup. That is to say, they were required to make spiritual preparation, and this involved reconciliation with both God and neighbour. There was a connection between their spiritual perception of Christ’s presence in the Eucharist and their calling and capacity to forgive one another. Another way of putting it is to say that by joining ritually and spiritually in Christ’s sacrifice, they were enabled to sacrifice their own needs for the sake of others’.

The 16th century Reformers wholeheartedly endorsed the first of these convictions, and it would be misleading to suggest that they entirely abandoned the second. However, they did begin a considerable downgrading of the ritual element of Christian life and its sacrificial import, a downgrading which their successors accelerated. By the late twentieth century, liturgical reforms of even the Roman Catholic Church shifted the emphasis of the liturgy from the ritual to the didactic: that the function of the Eucharist moved from a ritual participation in the sacrifice of Christ at an altar, to a community gathering around a table to propagate His “message” of forgiveness.

It is hard to deny that in the increasingly atheist bloc that was once Western Christendom, the formation of souls by liturgy is a dying art; hard, alas, to deny that this is true even within much of the Western Christian church. There are pockets of faithful who still order their lives around the more ancient and demanding liturgies, fasting and confessing in due season, but the authorities in the churches seem to be embarrassed by such zeal.

This North Western absence of sacrificial ritual is an exception to, one may even say an aberration from, the religious ritual practice of the rest of the world, whether it be among the Muslim nations, in India, or in any of the other many ancient religious traditions which the majority of humans continue to observe. The Westerners are the outliers. In a sense, we always were, since as Christians we had inherited the sublimated form of sacrifice as self-sacrifice, and thereby elevated forgiveness and servanthood to the highest of our virtues. We had been formed in those virtues by the ritual and spiritual demands of the Church year and especially by participation in the Eucharistic sacrifice.

Now, we have outgrown the ritual, but we have not stopped offering sacrifices. On the contrary, as our collective amnesia of our collective liturgical life spreads, and we forget that it is only in self-sacrifice that our true and everlasting Self can be found, we have all the more urgently to find someone else, some other self, to sacrifice. Hence the capitalist incentive to sacrifice anything and everything for one’s own purported benefit. Children, born or within the womb, women, the poor, animals and plant life seem to be the chief victims. One may sympathise with how the activist proponents of cancel culture pit themselves rather selectively against some of these sacrifices; but they fail, because ultimately they are operating in the same system, finding new victims to atone for the old ones. The alacrity with which sellers of consumer goods and even banks have taken up fashionable causes as marketing devices are a clear sign of this. Sacrifice was always a transaction between unequal powers. The God-man purified the sacrifice by removing its transactional element, for though he paid the wages of sin, He did so free of charge and of will. Ex-Christian nations have replaced our ritual participation in the once-and-for-all, liberating sacrifice of the Cross for slavery to an eternal cycle of retributive immolations. We held the key to eternal life and have broken it in the padlock to the chains of death.

This is where the West is trying to lead the world now. But it need not be so. We need not cancel others, because in Christ, God has cancelled Himself for us. Buried in Western tradition, hidden in the great stories of our past, are all the signs just waiting to be marked and inwardly digested by those whose eyes are opened to the reality of the cosmos as divine self-offering. It will take a liturgical and aesthetic renaissance to detach our gaze from the addictive array of shiny gods our screens offer us for the price of a fitting sacrifice, and recalibrate our eyes to the free gifts that lie hidden in plain sight, in our families, our neighbours, the mountains and the sea. There are places where this can still be done, eye-opening places which offer themselves at no price. We can still find beautiful houses of God, open to everyone for free, where we can participate in the one perfect sacrifice that sublimates them all and exposes their hidden meaning: that God’s free gift makes all transactions vain. That pure sacrifice is free self-gift in contrite heart and broken spirit.

Through fasting, repentance, and ritual participation, we can learn that the only effigy we need to burn is the effigy of ourself. Only then can the real self rise from the inner flame.

Masterful. Thanks so much.

Thanks for this thoughtful essay, and your response to Meg Nakano.

I better understood how, with our fellow-Hebrews, Christians recall that JHVH asks for 'mercy not sacrifice'; and that, for those who accept the message of Jesus Christ, our re-orientation is (or is called to be) profound.