Cor nostrum inquietum est donec requiescat in te.

Our heart is restless until it rests in Thee.

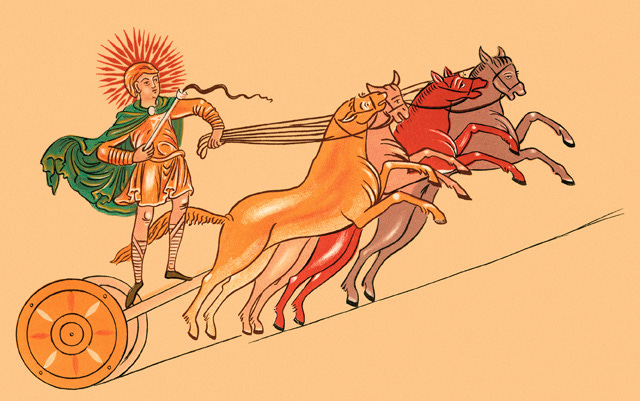

So St Augustine famously opens his Confessions, a book so beautiful and so readable despite its antiquity that I would recommend it every literate Christian. If one were instead (unwisely) to judge Christianity by modern Christian internet content, one might be forgiven for believing that the faith amounts to political activism, driven by a moralism of either progressive or reactionary flavour according to taste. St Augustine’s words are a prophylactic against this assumption. While there are indubitably political and moral implications to the Christian faith, they are derivative from it, and must not drive it. The Christian Way is above all a spiritual one, and it is towards a spiritual end that the wise driver wields the reins.

That end, as St Augustine surmises, is not activism, but rest. To get there may well involve struggle, heaving at times painfully to rein in wild and unruly horses. The heart will pump hard, be strained, sometimes pierced. But its destination is rest, and that rest can be found. God in Christ has made the inaccessible accessible, and beckons us there. But we will never find it unless our heart is set on it. We must not allow our hearts to forget it amid the bright signs and billboards that lure us off the straight and narrow path.

It is a commonplace that the Christian way is a pilgrimage, but no less true for that. St Augustine did not invent the route; he is merely one fellow walker along it, albeit one imbued with supernatural vigour. The pilgrimage began the day our first parents were exiled from Eden. They knew the rest of God, the shalom peace of Creation’s seventh day, but squandered it, choosing their own route, and so ours. Since then, we have lived at the break of the eighth day: whether at its eve or small hours, we cannot know, since it will break in an inverse eclipse that comes unexpected as a thief in the night.

Our pilgrimage is a return to something like Eden’s rest, and yet more than that. The letter to the Hebrews written in St Paul’s name relays it as a journey from Sinai to Zion, from the black and fiery mountain to the company of angels, from the gift of the Torah on tablets of stone to the heavenly city where it is written perfectly in every fleshly heart. Yet he also tells us how that journey, in strictly chronological terms, started even before Sinai. Every step of Hebrew history marks a recreation in microcosm, a new gift of peace after acts of human violence. Seth is a new creation after the destruction Cain waged on Abel; Noah’s Ark is a new creation after men and demons invited the destruction of the flood; by Abraham’s journey into the unknown, God creates a new nation from the remnants of men who offered sacrifice to idols; Isaac’s salvation from knife and pyre heralds the new life of resurrection; Joseph bequeathes his bones to the children Israel, knowing that they will be recreated with new flesh. And the vehicle of all these little re-creations is faith: not blind belief in commandments or principles, but the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen: a trusting heart in the God who calls, and by His Word unseen creates.

But our hearts are still as stone as tablets, lured by lying flesh that promises to soften them but leaves them colder and more wanting yet. We think the things that draw our hearts will fill them but, like St Augustine, find they only waken greater hunger. Their goods are only apparent, and evanescent. We rush upon beauties at the cost of never finding beauty itself. We gorge on meats, and the fatter we grow, the more we want. We indulge our lusts and find ourselves yet more lustful and more empty after. We gain wealth and the more we have the less it seems, the more we crave to meet our growing appetites. We hunger for justice and take our fill, but no resolution is ever enough, and what we suppose is a love of right becomes a mask for our lust for revenge. And in all this activity we miss the needful thing.

The Christian way is not an external moral code arbitrarily imposed to oppress our natural goodness, as the progressives say, or to subdue our fallen wickedness, as reactionaries suppose. It is not in the first instance a moral code at all. Talk of “Christian values” misses the point. It is the path to happiness, eternal happiness, in friendship with neighbour and with God. While we are servants of the divine will, this is subordinated to the higher calling of becoming what St Peter calls “partakers in the divine nature.”

St Augustine considered friendship the highest form of love. This friendship is God’s rest. To be a friend of God is to cease as God did from his own works. We must labour to enter into that rest, and work out our own salvation, but our labours will bear fruit only when we come to Him whose heart is meek and lowly, whose yoke is easy, whose burden is light and who grants rest unto souls. To be a friend of God is to let God work in us what is well pleasing in His sight, through Jesus Christ.

According to Our Lord, it is the pure in heart who will see God. His teaching to those who seek all moral perfections which come with that purity of heart is, “seek ye first the kingdom of God, and his righteousness; and all these things shall be added unto you.” So, do not seek “all these things” first. God will give you everything that you need to meet both your physical and spiritual needs if you set your heart on being ruled by Him, making it subject not to your whims, but to His gentle reign. For what God gives is nothing less than Himself. He gives Himself in the Law and all of Holy Scripture, but all the more, He gives Himself on the Cross, and He gives Himself in bread and wine.

God’s graceful knitting of the human heart to His Law into the human heart is not an act of litigation. The Torah (which is what St Paul means by “Law”) does indeed contain specific ordinances, thou shalts and shalt nots, but these are part of the Pentateuch’s overall story of pilgrimage. In both letter and spirit, they impact on the moral decisions Christians make around matters of generation, life and death, including abortion, euthanasia, and the limits of licit sexual practices. But the reason for that impact is not merely the arbitrary dictat of a superior legislative will. It is because there are behaviours which lead the heart to rest and comfort, and behaviours which lead the heart to want, hardness and turmoil.

Lest I be mistaken for reducing the Law and Gospel to psychological concerns, that is not what I mean at all. The “heart” of which the ancients speak encompasses the mind and imagination as well as the will. The whole person, our every device and desire, needs to join the rhythm of the sacred heart of Jesus if we are to find freedom from our cravings. The way to align our hearts with the heart of Jesus is to have the Torah written in ours as it is in His. The ancient fathers, St Paul among them, understood this as involving the memorisation of Scripture, at least in part. To take our daily bread in Scripture and, as the Prayer Book collect for the Second Sunday in Advent has it, not only to “mark” it, but “to learn and inwardly digest” it, is to have portions of it written in our hearts, ready for constant rumination. We become what we eat.

In meditating on Scripture, the Temple of our Body, which is the Body of Christ, becomes more than just a shadow of the Temple that is the heavenly Jerusalem, and takes solid, fleshly form. We become the place where all of Creation’s worship of God is concentrated, a fit vessel for His transfiguring Glory. We cannot achieve this alone, in the isolation of our hearts. St Augustine tried solitary approaches and gained only the most fleeting glimpses of God’s beauty. Only when he discussed the Scriptures with his mother were those two organs of Christ’s body knit into something greater, and given a more lasting vision of God’s rest. Likewise, it is by corporate rites that the Word made flesh prepares the ground of our hearts to be imprinted with His image. For it is Baptism into the self-gift of Christ crucified that we enter into the covenant of trust in Him; it is by frequent, prayerful reception of Holy Communion that we continue to pledge that trust anew and receive the grace to effect it. Christ alone, our teacher, priest, king, brother, friend, shepherd and trusty guide, can lead us through the shadow of the valley of death to the still waters where we may lay down our heads and hearts and rest.

For now, like the Beloved Disciple, we must rest our heads on His breast and listen to His heart, as it beats to the Torah’s cadence. We must do so together, in communion with one another and all the saints, so that it is not my heart, or your heart, our hearts in the plural, but our heart as one, the heart of the Body of Christ, that rests in Him. It is not about “being a good person,” as the non-religious sometimes and understandably suppose our aim to be, for only God is good. It is certainly not about moralism, and there is no shortage of recent events to show that the Church’s effort to police even its own moral conduct fall well short of the demands of the Torah. To follow the Torah and to be made good are possible, but only by co-operation with the grace of God received in Scripture and in Sacrament.

First, participate in God. The rest follows.

This is the best of your posts so far - accessible, applicable, and attractive in a city where the pace of work and study leaves many longing for the "behaviours which lead the heart to rest and comfort", amidst "behaviours which lead the heart to want, hardness and turmoil", even if their intent was indulgence or avoidance of productivity. Your beloved St. Augustine appears, but there is no danger of getting swamped in the Greek philosophers to whom many of us lack previous exposure.

A real treat, and worth developing further.

As a new Christian who chose an orthodox church, Anglican Catholic Church (just got confirmed yesterday!) this is something I love but am still wrapping my head around. The split of everything in society in Right and Left reflexively is difficult to unlearn. But as I put my focus on the message of universal love from God, it is becoming easier. Describing it to those outside orthodoxy is still difficult. This sermon helps me develop some talking points.