"Fear not: for I have redeemed thee, I have called thee by thy name; thou art mine." - Isaiah 43:1

One might expect the Catechism of the 1662 Book of Common Prayer to begin with God. It does not, or at least not directly. It begins with you.

In this, we see something of the genius of Christianity which is easily forgotten. The wise of the ancient world saw full well our need to love God. Plato's Symposium, perhaps the greatest pagan work on love, has Socrates recount the wisdom of the priestess Diotima, who makes love of the beautiful into a ladder towards the One and the Good. Aristotle saw desire for the good as almost a gravitational force, pulling all things to their proper end. The philosophers knew of our need to love God, or something like God. But what they could not acknowledge was that God also loves us.

Love for them meant a lack, a need, and if God was perfect, then He could lack nothing, and if He could lack nothing, He had no need of love. There is no room in this picture for St John's words that the Word became flesh, and so, God is love. There is no room for the God who calls His servants by name, who seeks out the lost sheep, who dwells among His people in fire and cloud, who becomes an infant clinging to His mother's breast, a lover of sinners, a forgiver of His own killers who hangs between two thieves and promises one Paradise; the God who says, "Abraham," "Peter," "Mary." This God would be known only by His self-revelation to the people of Israel, in their Holy Scriptures and in the person of Jesus, their Messiah and ours.

I think I have related before a strange tale that begins with the severed arm of an exiled king. In the early seventh century after Christ, Northumbria had passed back into the hands of pagan kings. Oswald, rightful heir, had been exiled to live among the Scots. There he was baptised and initiated into the faith of his fathers. In 634, he rallied his forces and returned to do battle with the pagan kings at Heavenfield. Setting up a cross at the battlefield, he prayed with his soldiers, and despite the enemy's superior numbers, he prevailed.

Oswald summoned the holy man Aidan from Iona to restore the Christian faith to his kingdom, giving him the Isle of Lindisfarne as his bishopric. The chronicler Saint Bede tells how one Easter feast, King Oswald, sitting with Saint Aidan, heard that poor people were gathering outside. The king instantly ordered the feast be taken to them and handed a silver platter to a messenger, telling him to break it into pieces and distribute it. Saint Aidan prayed that the hand which held that plate might be forever blessed.

Oswald eventually fell in battle against the pagan King Penda, who defiled his body by dismembering it to prevent proper funeral rites. But legend tells that a raven took up Oswald's arm in its beak and dropped it on a tree. That tree gave its name to Oswestry. The land around that tree grew fertile where blood dropped, and people dug the soil around it for its miraculous healing properties. They even dug a well, which remains in Oswestry today.

What does this strange story mean to Christians in England now? We may readily accept Biblical stories from far away places, but what of these more recent tales closer to home? Are they just medieval superstitions? Were people of old more gullible than we are? Perhaps we should forget what the Book of Common Prayer calls the "uncertain stories" of English saints and stick to the Gospel truth.

The Bible is certainly fundamental to Christianity. But there's a danger when learning the faith that we make it too general, too distant, something safely packaged in the past. This mistake has arguably accelerated Christianity's decline in our land. It need not be either/or – we can remember our local saints alongside Scripture. And that is exactly what we are meant to do.

Oswald's Tree does not exist in isolation. It is part of a much bigger story centered around another tree. The Welsh name for Oswestry, Croesoswallt, gives us a clue: not Oswald's Tree, but Oswald's Cross. The Cross on which Christ died is often called a "tree" in medieval hymns, and we might imagine Oswald's Tree as one branch of that great Tree which has spread, like a mustard bush, over the world. Even Oswald's mythological ancestry to Odin creates a link to the Cross, since Odin too was said to have died on a tree and risen again – a point Anglo-Saxon Christians recognized. Oswald's story points to what J.R.R. Tolkien called the "true myth" of Jesus Christ.

The Christian story is, in many ways, a story of trees. Let us go back to Eden, the story British children once knew. Through speaking His Word and breathing His Spirit, God created the world and carved out a glorious garden where He placed the first human. Eden was not a flat English garden but a high mountain place, hovering between heaven and earth, source of four great rivers, where death and sin were unknown.

God first created one human, because humans bear God's "image and likeness" and God is one. "Adam" simply means "the human" in Hebrew. But he was not meant to be alone. Eve was drawn from Adam's side – not from his foot, as though beneath him, nor from his head, as though above him, but to stand beside him as his equal. Though Scripture calls her his "helper," King David uses the same word for God in the Psalms – hardly a derogatory term. It means Adam relied on Eve, as we all rely on God.

This reliance, however, went famously awry at the forbidden Tree of Knowledge of Life and Death. Was this tree merely a test? It seems an odd thing for God to do, however much His ways may surpass our understanding. Adam and Eve's reaction, however, is entirely understandable. As any parent knows, banning something practically invites children to test boundaries. And who would not wonder about that forbidden fruit, right at the garden's centre?

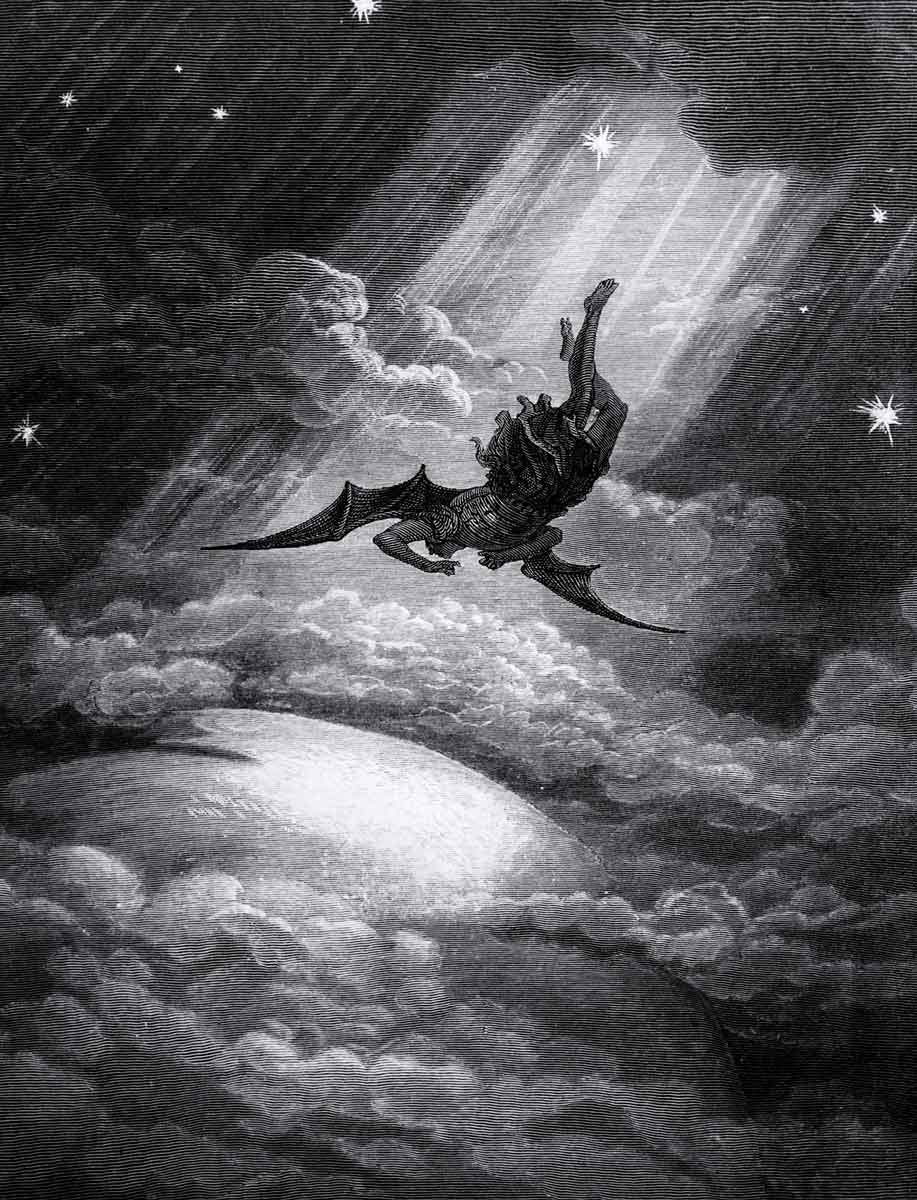

The story continues with the serpent – better understood as a dragon or supernatural being. The Hebrew word "seraph," which we know as a type of angel, actually means "snake." Ancient Jewish and Christian interpreters understood that certain angels had rebelled against God, refusing to bow to these new creatures of flesh and blood whom God seemed to love so much. The "snake" in Eden was likely one of these fallen angels – perhaps Satan himself, whose battle with the Archangel Michael St John saw in the Revelation granted to him, which makes up last book of the Bible.

When Eve and Adam ate the fruit, they gained knowledge at too high a cost – the cost of sin and death. It is like giving a knife or a smartphone to a child too young to use it wisely. Both have their uses, but one needs the maturity to use them. Likewise, the Tree itself was not evil – God makes nothing evil – but humanity took its fruit too soon, before we were ready or the fruit was ripe.

This ancient story connects directly to the wooden "Tree" of the Cross, by which the Dragon was defeated and humanity restored to eternal life. Throughout Scripture, wood carries this salvific symbolism: Noah's ark, Moses' staff, the Ark of the Covenant – all wooden objects carrying God's people through hostile lands toward promised salvation.

These connections do not end with the Bible. Christianity is not just about universal principles but also about the particular – about families, parishes, and nations. In England, we have our own stories and our own trees connecting our land to Eden and Jerusalem.

When Oswald's blood dripped from that tree and sanctified the land, it wasn't because he was a pagan "god" but because, as a saint, he participated in Christ's holiness. His generosity partook of Christ's love for the poor. His battle against pagans shared in Christ's struggle against evil. His blood nourished the earth as an extension of Christ's blood. His life was a sharing in Christ's life, his death in Christ's death.

The first question of the catechism – "What is your name?" – may seem trivial, but it is profoundly important. Our Lord said, "I have called you by name; you are mine." He described himself as a shepherd knowing each sheep by name. When we receive a saint's name at Baptism, even though chosen by our parents, that is the name by which Christ has called us. Through them, He has given us our names.

Pay attention to your Christian name and the saint whose blessings that name carries. By sharing that name, you share in that saint's particular mission, their unique way of revealing Christ. No single saint perfectly represents Christ – only He perfectly reflects God's image. But each saint reflects certain aspects of that image, like individual squares of a mosaic which, viewed from a distance, reveals the full picture.

What applies to saints applies to us. All Christians should aspire to sainthood – not through some generic pattern, but in the particular way Christ calls us. He calls us by name, by parentage, by nation: St. Hugh of Lincoln, St. Hilda of Whitby, St. Margaret of Antioch – all known by their land as well as their names.

Research your Christian name, your local saints, and your parish church's namesake. Each has a saint's day marked in the Book of Common Prayer's calendar – days for prayer, communion, feasting with family and friends, pilgrimages, perhaps even praying at saints' relics destined for Resurrection.

Christianity should be a religion of joy. You have been blessed with a name. Celebrate it!

🌳 Thank you Father, grace and peace to you on the Sunday of the Samaritan Woman at the well. Call upon the Holy Name, Christ is RISEN!